Sister Tempest: A Frequently Strange And Often Wonderful Cyclone Of Creativity

Indie writer/director and strange cinema guru Joe Badon returns with his sophomore feature, Sister Tempest. True to it’s name, Sister Tempest unleashes a relentless, ever-flowing cyclone of creativity. It may be too bizarro for many conventional moviegoers to get behind, but the messy kaleidoscopic phantasmagoria Joe Badon whips up is more than enough for adventurous cinephiles seeking something weird and psychological to sink their teeth into.

Anne Hutchinson's troubled relationship with her missing sister is under alien tribunal. Meanwhile, her new roommate's mysterious illness causes her to go on a cannibalistic killing spree.

Imagine an Alejandro Jodorowsky directed version of Albert Brooks’ 1991 comedy Defending Your Life that collided with a hybrid of David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire. Now, imagine that film being blended up into a chunky paste alongside old-school kaiju & sci-fi flicks and newer-wave bizarro horror cult classics (a la The Greasy Strangler or Rubber). Garnish it off with a dash of Troma, a pinch of the Andy and Charlie (no relation) Kaufman, a heavy dose of the cartoonish, and a hit of LSD, and you’re in the realm in which Joe Badon’s frequently strange and often wonderful Sister Tempest resides. It’s a film that defies easy categorization or description, and it’s such a relentless flood of ideas and images that it’s sometimes hard to stay afloat, but if you can surrender to Badon’s highly imaginative onslaught, you’ll be rewarded with the weird and awe-inspiring oscillation of its waves.

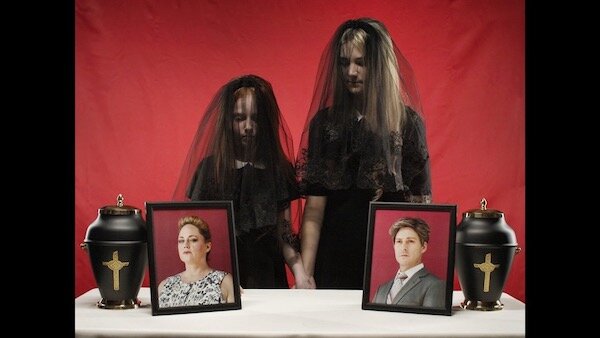

On the surface, it’s a tale about a troubled woman, Anne Hutchinson (Kali Russell), distressed over the recent disappearance of her sister, Karen (Holly Bonney), whom she vowed to never leave and always watch over following their parents’ untimely death (as shown in the film’s prologue). But things are hardly as straightforward as they seem (or are they?); Anne’s surmounting grief and guilt over Karen’s absence sparks some strange happenings, least of which is the alien tribunal overseeing Karen’s disappearance. There’s Anne’s new roommate, humorously named Ginger Breadman (Linnea Gregg), who temporarily fills the Karen-sized void in Anne’s life and ultimately serves as Karen’s double. Although Ginger appears to be a seemingly benign “potato person” from Idaho, she’s really a crazed cannibal with a mysterious illness and malevolent intentions. Meanwhile, there’s also an “eternal cosmic camera crew,” a 50-ft astronaut, an interdimensional gatekeeper, a bit of romance, and whole lot of striking tableaus. Strange as they may be, all disparate threads eventually tie to a knot.

While there’s certainly a lot — perhaps even a bit too much — going on in Sister Tempest, its plot remains relatively simplistic. Once all its obscuring clouds finally dissipate, the reality of the film becomes clear. As we separate the truth from the distortions, we begin to see the film as a fractured presentation of Anne’s crumbling mental state as she copes with her loss, grapples with her actions, confronts her denial, and seeks absolution. Much in the same way that Robert Wiene uses sharp, jagged shapes and oblique lines to visually represent the twisted warp of The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari’s narrative framing, Badon uses all the formalistic elements of cinema to visualize the whirlwind of unhinged emotions and feelings swirling inside Anne. Its manifestation takes the form of a kaleidoscopically cacophonous nightmare, psychedelic-tinged and soaked in surrealism and schizophrenia.

Clocking in at two hours, the film’s length is one of its biggest pain points. It’s not that it can’t fill the time — Badon and company clearly can; it’s that not all of its length is justified. While many of Sister Tempest’s digressions are enjoyable to watch, they’re not all vital or in service to its threadbare plot. Certain tangents muddy the waters and dampen some of its punch. Tonally bonkers, the film rarely ever settles down and breathes either; it just goes and goes and goes, fragmented into disorienting shards and sporadically bouncing from idea to idea with the brake lines severed. Without many breathers along the way, its two-hour journey definitely teeters on the point of exhaustion and will test the stamina of many viewers. Still, no matter how relentless it can be, we were always awestruck by it never-ending creativity. The cinematography from Daniel Waghorne is a real joy to behold, as are the sets and costumes. Joseph Estrade also works wonders in the editing, creating some truly disorienting effects while also keeping fairly tight reins on this unhinged phantasmagoria.

When the dust settles, Sister Tempest doesn’t travel much narrative distance, but it certainly takes you on a relentlessly wild rollercoaster ride. While its self-indulgent gonzo outpouring of creativity and imagination can be daunting, its form follows its function, and it’s justified when the smoke clears. However, its longer-than-necessary runtime partially obscures the journey and may prevent some viewers from crossing the finish line. One thing is for certain: Joe Badon is overflowing with ideas and images, and we cannot wait to see the next slice of strange cinema he serves up next.

Recommendation: The film isn’t available anywhere at the moment, but if you’re into avant-garde Arthouse in the vein of David Lynch or Alejandro Jodorowsky, you should definitely put Sister Tempest on your radar and seek it out when it becomes available.

Rating: 3.5 alien tribunals outta 5.

What do you think? We want to know. Share your thoughts and feelings in the comments section below, and as always, remember to viddy well!